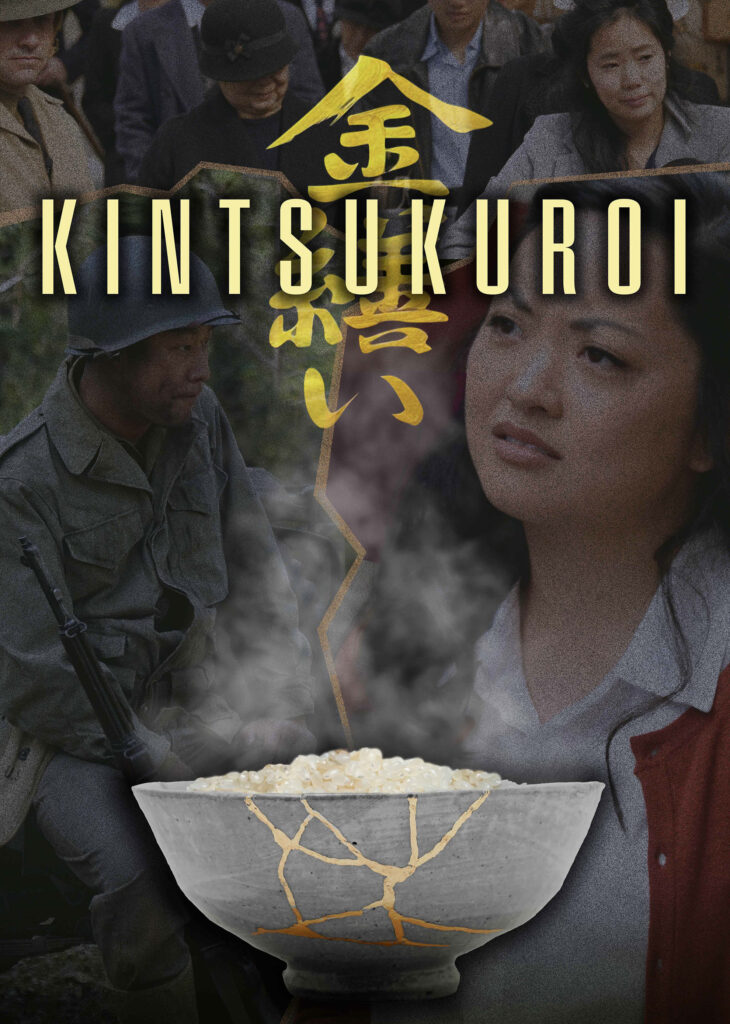

In Japanese, meaning “golden repair,” Kintsukuroi refers to the traditional art of mending broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum—and it’s also the perfect metaphor for Kerwin Berk’s sweeping historical epic. Set in the 1940s, the film follows a Japanese American family fractured by U.S. wartime politics, and against all odds, it truly shines. Despite an extremely limited budget, writer-director Berk has crafted a compelling, two-plus-hour historical drama on Japanese American internment with a level of intimacy and emotional truth rarely achieved—and certainly not with this kind of personal urgency. Even with my usual resistance to historical epics, I was completely glued to the screen from the first frame to the last. Kintsukuroi doesn’t just tell history—it repairs it, filling its fractures with empathy, humanity, and quiet gold.

After seeing Kerwin’s Facebook posts about his latest feature, I reached out, and he was kind enough to share a screener with me. As an Asian American filmmaker who began my career in the early ’90s, I was exposed to the subject of Japanese American internment long before it became a fashionable point of historical reference—starting with my first internship at Visual Communications, the nation’s oldest Asian American media arts organization, in the summer of 1989.

Coincidentally, that was also the moment when Alan Parker was preparing his Hollywood feature Come See the Paradise. In an effort to sidestep accusations of racism, the studio invited Asian American media organizations to consult on the production. The gesture, however, rang hollow. I distinctly remember Amy Kato, then an associate at VC, returning from a meeting visibly unimpressed—after Parker reportedly joked about casting Meryl Streep as the Japanese American female lead.

The role ultimately went to Tamlyn Tomita, but the episode lingered with me as an early lesson in how Hollywood so often approaches Asian American history: with curiosity, calculation, and an alarming ease toward erasure. A couple of years later, as an undergraduate at Berkeley, I finally caught Come See the Paradise and found it hollow and impersonal—another familiar Hollywood exercise that centers a white savior, this time embodied by Dennis Quaid.

Flash forward to 2025. Thanks to the democratization of technology, an independent filmmaker like Kerwin Berk can now mount a sweeping, emotionally resonant historical saga on a shoestring budget—powered by a stellar volunteer cast working entirely outside the Hollywood system. Having followed decades of discourse around Japanese American internment—a subject that remains painfully relevant—I can honestly say I’ve never seen a dramatic feature tackle it with such confidence and restraint.

What sets Kintsukuroi apart is its refusal to lecture. Instead, Berk frames history through an intimate, human lens, transforming a specific cultural trauma into a universal story about family, survival, and resilience. It is precisely this personal yet expansive perspective—rooted in Berk’s identity as a Japanese American filmmaker—that makes Kintsukuroi not only the most compelling film ever made on the subject, but one that finally feels whole, repaired with empathy rather than rhetoric.

I don’t want to oversell the film. Ultimately, as a filmmaker myself, I’m simply struck by the assurance and ambition of Kerwin’s work. With this impressive second feature, he delivers a sweeping historical epic that is deeply personal and beautifully told—proof not just of a subject mastered, but of a filmmaker coming fully into his own.